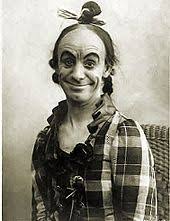

Baldwin's Catholic Geese, Keith Hutson's recent collection from Bloodaxe (2019), is a double collection, in more than one sense. It weighs in, at 118 pages, as a collection twice as long as your average slim volume. But it is also double in another sense: two-natured, bipolar, both wings and spotlight. Seen in one light, it's a comic tour-de-force, full of great jokes, novelties, ditties: Percy Edwards's imitation of a Kookaburra, Buster Keaton's early incarnation as 'The Human Mop.' Lit from another angle, it's full to bursting with shadows, fallings-off, blight, poverty: the dying Leslie Hutchinson selling his once gorgeous body in Paddington or nineteenth-century backdrop-painter Richard Dadd painting 'pixies, weeping on the walls' of Broadmoor, after stabbing his father in a moment of insanity.

Full to bursting. That's why it would be wrong to categorise this as a long book. It isn't. It's a fat, rich, deep trove of voices and presences. It's a suitcase stuffed with band-parts, costumes, material, illusions, tricks of the voice or the light. It's a whole world made up of the most glorious troupe of minor characters, brought to life by a poet who has a chameleon-like ability (Keats called this sort of thing 'the poetical character') to become just about anyone, and, simultaneously, to muster a kind of compassionate detachment from those he evokes.

The result is a kind of theatrical Odyssey through more than two centuries of theatre-history, where even the more historically remote characters seem just as present as those who died only recently. There is a glorious compression of time, and, as a result a giddy sense of its emptiness. The word that's watermarked into this large canvas, a bit like the skull in Holbein's 'The Ambassadors,' is vanitas. The sense of vanitas echoes through every piece. Take Hutson's masterful poem 'The Audience,' detailing Hutson's encounter with Les Dawson. At the outset, the famous comedian and TV host seems stubbornly unlikeable, the kind of man who uses his fame and status to force you to buy him the 'double scotch.' And yet, by the close of play, as Dawson fades out, slurring, away from view, he seems to possess the dignity of someone Dante spoke to, the shade of a being we forgive for disappointing us.

The skill involved in this is striking. This is a poet who is brilliant at dialogue, and at concentrating and distilling human speech, suggesting a life--or a death-- in a line, or half a line. Perhaps this is the writer's ultimate skill, the one Berryman so praised Shakespeare for: to be able to suggest even a minor character's whole story in a single, seemingly throwaway, comment. Here's the ending to 'The Audience,' where Hutson, then a young comedy writer, says goodbye to Dawson:

We almost hugged, then you had to push off

to do your stuff. I hoped you could use mine.

Nothing's impossible, you said, from far away.

Yet, thanks to the generosity behind Baldwin's Catholic Geese, none of the characters, no matter whether obscure, funny or unfunny, or downright sad, feel far away. Nothing in this lost world feels neglected, not even that generic dullard, the 'Straight Man' of the comedy duo, part Ernie Wise, who buttonholes us:

Try this for size: the difference between us,

you and me, is I pretend I'm dull.

And that barrel of laughs who acts

like he should be locked up--

he is. Try being the key.

These poems are acrobatic like that, turning on a dime, turning verbal somersaults, but so nonchalantly they belie the practiced ear and eye of Keith Hutson. Equally in evidence, in Baldwin's Catholic Geese, is not only the elegant song and dance of these poems, but also their darkening downstage knowledge, the parry and hit-home of their asides.

Comments

Post a Comment